Plantar fasciitis remains one of the most common causes of chronic heel and foot pain in adults. It often affects people who spend long hours standing, engage in repetitive impact activity, or experience age-related tissue changes.

As research into regenerative medicine expands, a focused question continues to appear in scientific literature: can stem cells help plantar fasciitis and related foot pain conditions, or does the evidence remain limited?

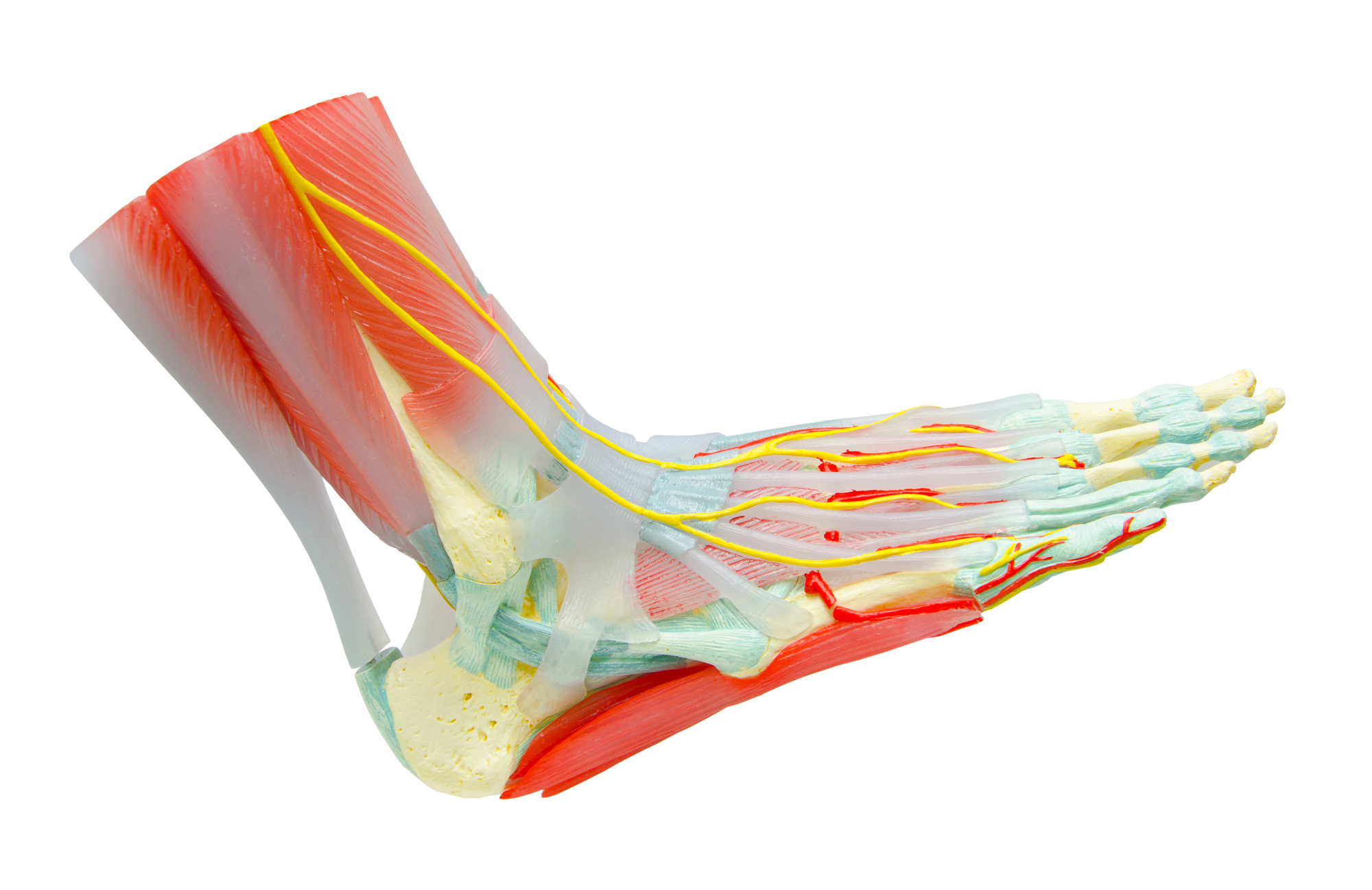

Plantar fasciitis involves irritation and structural change in the plantar fascia, a thick band of connective tissue running along the bottom of the foot. This tissue supports the arch and absorbs mechanical load during walking and standing.

Chronic plantar fasciitis often shows less active inflammation than once assumed. Imaging studies frequently reveal collagen disruption, thickening, and reduced tissue elasticity. These findings have shifted research attention toward degeneration and impaired repair rather than short-term inflammation alone.

Because connective tissue heals slowly, persistent microstrain may exceed the body’s natural repair capacity. This helps explain why standard approaches sometimes reduce pain without restoring tissue quality.

Stem cells draw research interest because of how they interact with damaged or stressed tissue environments. Rather than acting as direct replacements, many stem cells studied in musculoskeletal research release signaling molecules that influence inflammation, blood flow, and local cell behavior.

In the context of foot pain, researchers study whether these signaling effects might support tissue remodeling or alter pain pathways. Research on regenerative therapy for foot pain often focuses on how the plantar fascia responds to biological cues rather than mechanical correction alone.

This shift reflects a broader trend in connective tissue research. Scientists increasingly examine cellular communication instead of isolated structural damage.

Published research on stem cells and plantar fasciitis remains limited and exploratory. Most available studies involve small participant groups or early-stage clinical designs. Some report improvements in pain or function, while others show minimal change compared with baseline measures.

Several papers describe symptom relief without clear evidence of full tissue restoration on imaging. This pattern suggests that changes in inflammation or nerve sensitivity may explain reported benefits rather than complete structural repair.

Systematic reviews indexed through PubMed often emphasize variability and short follow-up periods. Researchers consistently call for larger studies with standardized outcome measures.

Research on regenerative therapy for foot pain uses layered methods. Laboratory studies examine how stem cells interact with tendon-like tissue and inflammatory signals. Animal models help researchers observe tissue response under controlled loading conditions.

Human studies often measure pain scores, walking tolerance, and imaging changes over time. Safety monitoring remains central, as researchers track immune responses and unintended tissue effects.

Importantly, studies vary in how they define success. Some focus on symptom relief, while others prioritize imaging findings. This lack of uniform endpoints complicates comparison across trials.

Variation appears consistently in stem cell injections for foot conditions research. Plantar fasciitis itself does not present uniformly. Some people experience focal heel pain, while others report diffuse arch discomfort.

Tissue quality, circulation, body weight, and gait mechanics influence how the plantar fascia responds to any intervention. Age and metabolic health may also shape cellular signaling and repair capacity.

Stem cells respond to their environment. A tissue with ongoing mechanical overload or advanced degeneration may react differently than one with mild structural change. These factors help explain why published results show broad ranges rather than predictable outcomes.

Despite growing interest, evidence for stem cell injections for foot conditions remains scarce. Few large randomized trials exist, and long-term follow-up data are not widely available. Many studies lack comparison groups that allow clear separation between placebo effects and biological response.

Researchers also highlight that pain improvement does not always match structural change. Reduced pain may reflect altered nerve signaling or inflammatory tone rather than lasting tissue repair.

Foot pain research increasingly recognizes that tissue health depends on more than isolated structures. Load distribution, muscle strength, systemic inflammation, and recovery capacity all interact.

Stem cell research fits within this broader framework as one area of investigation. It does not replace mechanical, metabolic, or lifestyle considerations that influence plantar fascia stress.

Current evidence suggests that stem cells for plantar fasciitis research remain exploratory rather than definitive. Some studies indicate potential symptom improvement, while others show limited or inconsistent effects.

The scientific literature reflects a field still refining its methods. Researchers continue to study which tissue environments respond, how outcomes should be measured, and which variables influence durability.

For people researching chronic foot pain, this perspective helps align expectations with how scientists describe their findings rather than how treatments are sometimes marketed.

Research into regenerative medicine, inflammation, and connective tissue health continues to evolve. Interpreting this research requires careful reading of studiy design, limitations, and biological context.

Cellebration Wellness provides education-focused resources that explore cellular health, chronic pain science, and aging from a research-informed perspective. If you would like to learn more or schedule a general wellness consultation centered on education and guidance, you are welcome to contact Cellebration Wellness at (858) 258-5090 today.